Christmas Seals

It was December 9, 1907, when a woman in a Red Cross uniform, sat at a table in the Wilmington, Delaware post office to sell envelopes stating the following:

25 Christmas Stamps

One penny apiece

Issued by the Delaware Red Cross to Stamp Out the White Plague

Put this stamp, with message bright, on every Christmas Letter; help the tuberculosis fight, and make the new year better.

These stamps do not carry any kind of mail, but any kind of mail will carry them.

The idea to sell stamps to raise awareness of the plight of tuberculosis patients was discovered in a magazine story read by Miss Elizabeth Bissell, Secretary of the Delaware Red Cross. Bissell read about the enormous success the people of Denmark had in raising funds, which prompted her to take a similar action.

Within a few weeks, the Christmas Stamp of 1907 was a roaring success. Selling nearly 80,000 copies, they made over $3,000 and immediately set to work on a 1908 stamp. In 1908, the year of their first nationwide sale, the group raked in $135,000. By 1916, they had their first million-dollar year and by 1941, the total sold was $114,000,000.

Tuberculosis has been around likely since before the written word. It wasn’t until 1882 that the cause of tuberculosis was discovered by Robert Koch. When Wilhelm Roentgen created the x-ray in 1885, evidence of tuberculosis could be seen without an autopsy. A considerable amount of the Christmas Seal funds were spent on x-ray chest pictures for high school and college students and various adult groups. Early discovery, as it was deemed, was the best way to quickly stop its spread.

From folk cures and incantations to scientific methods, it was finally determined in the 1840s and 1850s that fresh air and rest were the two best ways to combat the disease. By 1904, a group of physicians had gotten together and formed the National Tuberculosis Association, dedicated to eradicating the deadly disease. Unfortunately, they couldn’t raise enough public awareness, and funds, to conduct their research. That’s when the Christmas Seal stamp popped up.

Stamps like the Christmas Seal were used to varying levels of success as early at the 1860s. In 1863, stamps were created to help improve Union camp conditions during the Civil War. In 1897, New South Wales issued a stamp to aid a “Consumptive Home” and in 1904, a Danish postal clerk created and sold his own Christmas Seal, selling more than 4,000,000 stamps to benefit children with tuberculosis in Denmark and continuing through 1907 when Elizabeth Bissell read about it in a magazine.

In 1910, the National Tuberculosis Association and the Red Cross formed a partnership. The Red Cross would sponsor the Christmas Seal production and sales, and the National Tuberculosis Association would distribute the funds to where they would do the most good. This would often be under one of four general heads: Education, Case-finding and Treatment, Rehabilitation, and Administration. With funding coming from everyday people all the way up to government entities, it’s no wonder these campaigns raised such incredible funds, and saved the lives of millions of people.

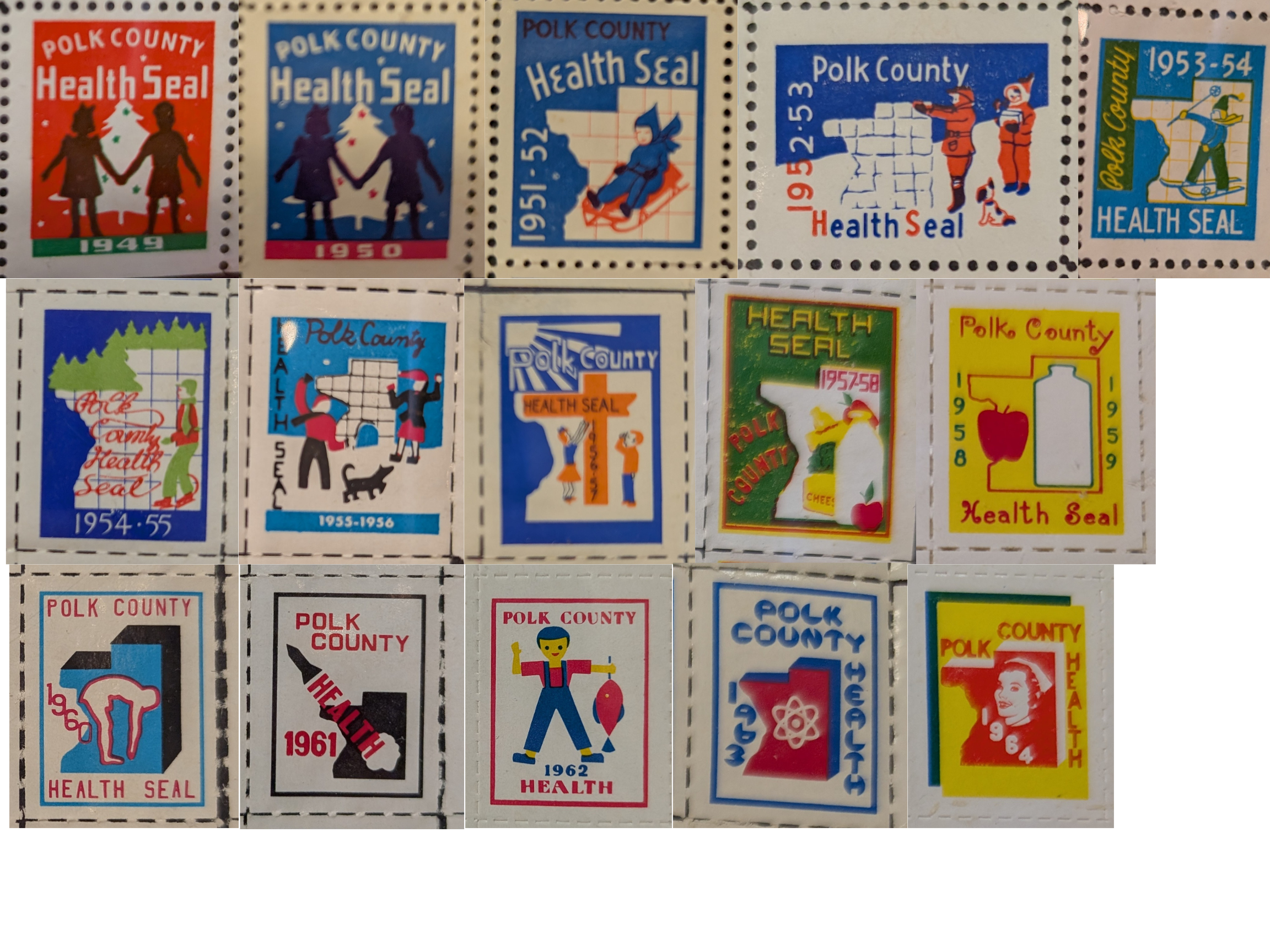

Polk County Health Seals

In a similar fashion, county health departments created their own seals that could be sold during the Christmas season and the funding would help with county public health

needs. The Polk County Health Seals were designed by students at Polk County Schools as early as the 1951–1952 school year and running through at least 1978. The seal, which is distributed and sold shortly before each Christmas season, is a seal to be used throughout the entire year. This is the reason the seal carries the date for the year following its distribution and sale.

To encourage participation and interest in designing the seal, a poster contest was open to all students in 6th, 7th, and 8th grade at Polk County Schools. It was sponsored by the Polk County Health Council. Each school district was invited to enter their best six posters, and judges would be selected to choose the three winners from all the county's entries. The Polk County Health Council awarded steadily increasing prize money to winners with $25.00 to the first-place winner, $15.00 to the second-place winner, and $10.00 for the third-place winner in 1975. This is equivalent to $155.00, $93.00, and $62.00 in today’s currency. The first-place winner would also receive the honor of having their seal design used on the health seals throughout Polk County.

Sales of health seals averaged $1,300.00 throughout each year, which is equivalent to $8,400 in today’s currency.

Winners over the years include:

· 1952: Carroll Klockeman (Alec A. Johnson School)

· 1953: Carroll Klockeman (Alec A. Johnson School)

· 1954: Renie Peach (Milltown School)

· 1955: Gerale Roe (Balsam Lake School)

· 1956: Sarah Hellerud (Milltown School)

· 1957: Valdis Vavere (Milltown School)

· 1958: Gary Knerr (Amery School)

· 1959: Gloria Floreen (Balsam Lake School)

· 1960: John Nielsen (Centuria School)

· 1961: Marsha Grant (Balsam Lake School)

· 1962: Mary Jensen (Luck School)

· 1963: Billy Nichols (Milltown School)

· 1964: Pam Boughton (St. Croix Falls School)

· 1965: Dick Soderburg (Dresser School)

· 1966: Diana Cruthers (Oak Hill School – Luck)

· 1967: Kay Friberg (Frederic School)

· 1968: Sherri Anderson (Frederic School)

· 1969: Sandra Wilson (Frederic School)

· 1970: Mona Hochstetter (Frederic School)

· 1971: Karen Java (Frederic School)

· 1972: Susan Hansen (Amery School)

· 1973: Robert Janis (Amery School)

· 1974: Barbara Bieniasz (Amery School)

· 1975: Judy Fox (Osceola School)

· 1976: Cheryl Peterson (Amery School)

· 1977: Lisa Lundeen (Frederic School)

· 1978: Jeff Rutcosky (Amery School)

Sources:

Hodges, Leigh M. 1942. The People Against Tuberculosis: The Story of the Christmas Seal. National Tuberculosis Association.

Polk County Department of Public Health. 1975.